A little more than a year after the European Union launched its tax haven listing process, EU member states face crucial political decisions in 2019. They include whether or not more than 50 countries or independent territories currently on a “grey list” have met their commitments to avoid being put on a blacklist.

In addition, the EU finance ministers are expected to expand the geographical scope beyond the 92 countries that have already been screened. Also new tax haven criteria including transparency rules related to company ownership and fair corporate taxation are due to be adopted.

And, in what will likely be the most politically sensitive issue for the tax haven process, EU member states must decide whether to list United States if it does not agree to adopt by June the OECD Common Reporting Standard concerning exchange of banking data.

EU tax haven process critics who insist the process has been nothing more than a paper tiger can point to the six relatively obscure countries or territories currently blacklisted. What started out as a list of 17 in December of 2017 is down to six. Besides the U.S. Virgin Islands, the others, including Samoa, American Samoa, Guam and Trinidad and Tobago have insignificant financial centers. No EU member states are listed, which many tax advocacy groups such as Tax Justice Network, Oxfam International and Transparency International insist is a major flaw.

The current criteria used by the EU in determining whether or not 92 countries or independent territories are blacklisted includes transparency rules involving the exchange of banking information, including the OECD Common Reporting Standard (CRS). The second set of criteria involve “fair” corporate tax policies. The EU Code of Conduct Group for Business Taxation, made up of EU member states officials and excludes European Parliament participation, have the final say on what countries end up on the EU list.

Although the current EU tax haven blacklist only contains six countries and jurisdictions, the EU member states agreed a year ago to establish the grey list.

A crucial issue for those on the grey list includes how EU member states will deal with jurisdictions that have zero corporate tax rates such as those in the Channel Islands. They must decide whether companies that benefit from zero corporate tax rates have substantial “economic substance” to justify their presence. The EU goal is to clamp down on letterbox companies.

The Cayman Islands, which is one of the world’s largest offshore centers for fund management, is on the EU gray list and also has zero corporate tax rates. It recently adopted “economic substance” requirements for any company that uses its territory for its headquarters.

The new laws adopted by the Cayman Islands in 2018 are indicative of how the EU tax haven listing process has triggered change. Of course, the British Parliament decision taken in March of 2018 to require all U.K. overseas territories to adopt company beneficial ownership registers has also been a motivator for reform.

Another key, but as yet unresolved issue, for 2019 concerns sanctions that should apply to countries on the EU tax haven blacklist. To date EU member states have discussed a range of measures including imposing withholding taxes on any funds moved from the EU to a blacklisted country.

Aside from the gray list decisions as well as those dealing criteria and sanctions, the EU member states face intense pressure from the European Parliament to drop the de facto political exemption it has allowed the U.S.

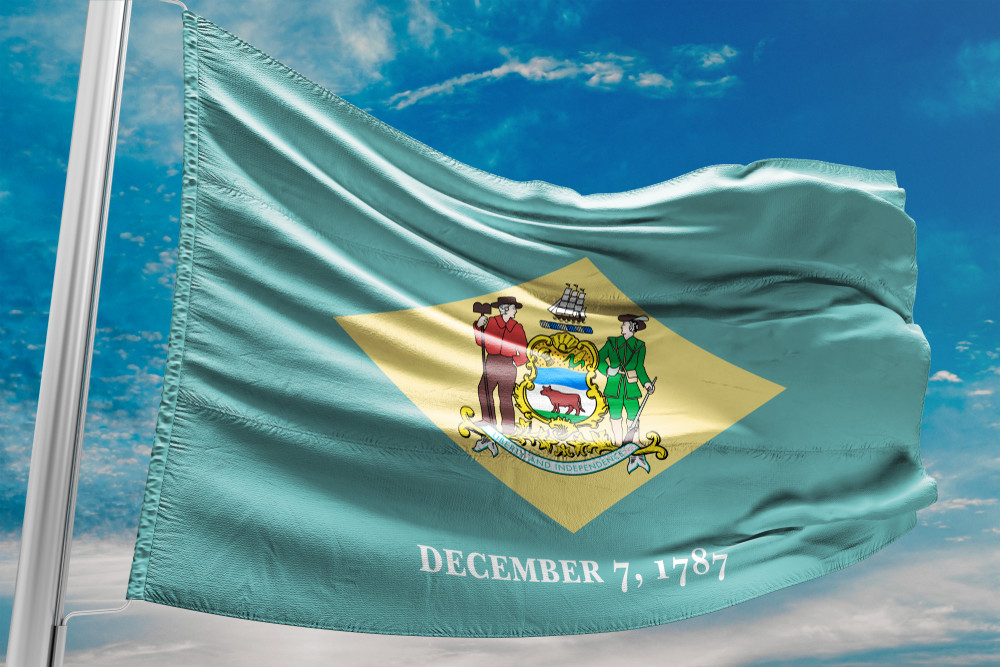

EU parliamentarians as well as tax advocacy groups insist the U.S. has become the new go-to tax haven, especially as the more traditional offshore financial centers have been forced to tighten rules as a result of pressure from the EU. Currently not only does the U.S. not have bank account information exchange requirement for non-residents but some states led by Delaware have no company beneficial ownership rules.

Another highly sensitive decision the EU member states must take concerns Switzerland. The neutral, landlocked alpine nation is currently on the EU gray list because it exempts from tax multinational company profits earned outside of Switzerland. Attempts by Switzerland to revise the corporate tax laws for multinational companies, including in a referendum held in 2017, have failed.