Two years ago Paul Tang, a Dutch European Parliament member and foremost expert on tax legislation as well as corporate tax evasion, showed up at U2 frontman Bono’s mansion in Dublin to return a “letterbox.” The publicity stunt was designed to underline how U2’s and thousands of other companies avoid paying taxes by using Dutch laws to shift profits.

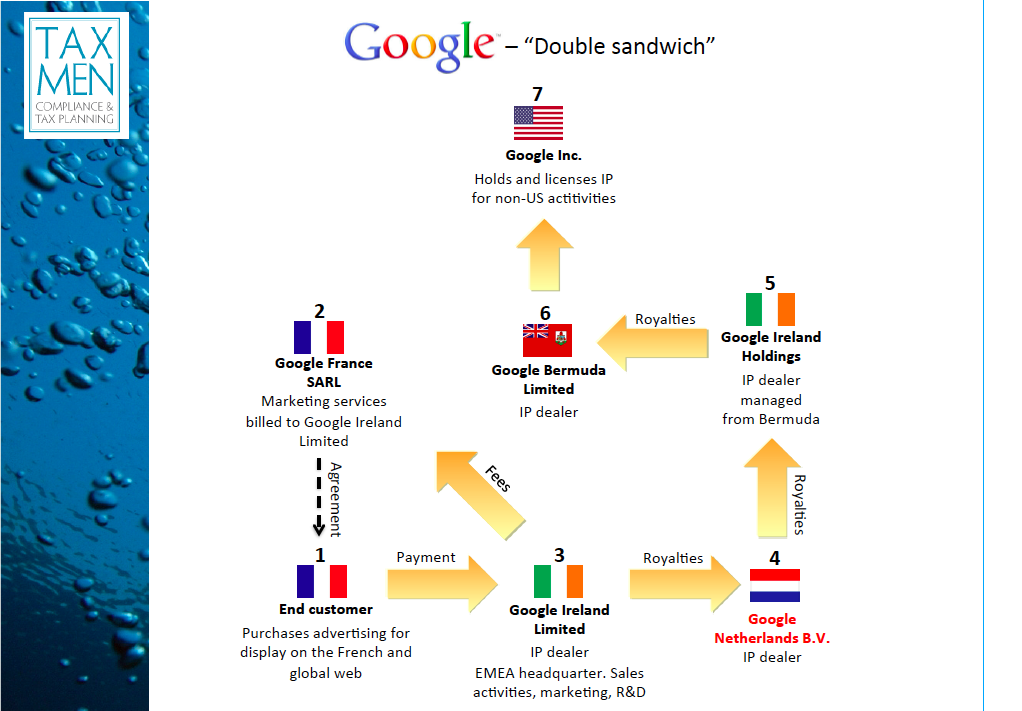

As the Netherlands‘ leads the charge against a possible eurobond to help prevent a European Union economic, political and social collapse, those lax tax laws – one version of which has been illustriously referred to as a “Double Irish and a Dutch Sandwich” because companies shift could profits through the two countries into tax havens – are back in the firing line. Incensed by the Netherlands’ proselytising that a eurobond will only promote “moral hazard” in some debt-ridden EU countries such as Italy, the Dutch government has in turn been accused of using “unethical” tax laws. These laws, they say, have deprived for decades southern European countries of desperately needed health care, education and other social service revenue.

Those complaints were spelled out in no uncertain terms by Italian European Parliament member Carlo Calenda and signed by 12 local politicians in a March 30 letter urging Germany to drop its opposition to a eurobond. And certainly the Dutch tax haven complaint is not one harbored by Italian officials alone. Portugal and Spain have consistently complained in recent years because some of their largest listed countries have their corporate headquarters in the Netherlands in order to cash in on the nation’s sweetheart corporate tax laws.

But in all fairness, it has to be noted that the Dutch government has adopted significant tax law legislative changes in recent years to prevent companies from using the country to shift profits offshore to tax havens. The effort began under the EU Dutch presidency in 2016 when OECD BEPS legislation was approved by EU finance ministers after the Panama Paper revelations galvanized action. The most important of those laws was the EU Anti-Tax Avoidance directive (ATAD) that included a host of measures including restrictions on controlled foreign companies, debt financing tax reductions and exit taxation as well as anti-abuse rule that gives tax authorities enhanced powers. That legislation took effect in 2019 and its impact will be known later this year.

Two other Dutch tax legislative changes have recently been adopted and are taking effect in 2020. One involves the so-called EU ATAD 2 that restricts hybrid mismatches designed to crack down on double non taxation that occurs when two countries exempt a dividend, royalty or license fee payment. When the law was approved in 2017 Dutch Finance Minister Jeroen Dijlessbloem, facing intense political pressure from other EU countries, finally lifted his objections. But in doing so he insisted the law would have a significant impact in lost tax revenue and jobs in the Netherlands.

Another new Dutch law will require withholding taxes on dividend and other payments made from Dutch corporations to countries or jurisdictions on the EU tax haven blacklist.

Despite these changes the European Commission insisted as recently as February that “evidence suggests that the Netherlands ‘s tax rules are used by companies that engage in aggressive tax planning.” According to a recent International Monetary Fund paper the Netherlands is the world’s second biggest recipient of foreign direct investments made through “special purpose entities” such as the Dutch sandwich. Luxembourg is No. 1 on the list and, according to the IMF, the two countries host nearly half of the world’s letterbox companies.

The Netherlands is also prominent on the London-based tax advocacy group Tax Justice Network‘s Corporate Tax Haven Index and its Financial Secrecy Index. The Dutch nation is no. 4 on the 2019 Corporate Tax Haven Index and no. 8 on the 2020 Financial Secrecy Index.

And Tang himself has made it clear he supports the renewed criticism against the Netherlands and its tax laws.

“The tax avoidance industry in the Netherlands is at the direct disadvantage of its European partners,” Tang said. “It costs billions of euros each year.”

Tang also predicted that when the corona crisis is over the issue of not only the Netherlands tax laws but those of other infamous EU member state countries such as Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta and Cyprus will face more pressure than ever because of the desperate need by other countries to finance huge public debts and budget deficits.

The intensity of the backlash against the Netherlands has forced the government to climb down from the moral hazard high horse. At least for now. Whether it means the Dutch government, along with Germany, Finland and Austria, will relent on their opposition to euro bonds should become clear on April 7 when EU finance ministers meet. They will try to find a solution that EU heads of state and government could not when they held a video conference March 26.

Such is the scale of the COVID-19 crisis, that it could ultimately decide the fate of the European Union‘s future tax legislation.